First Ladies, Second Acts

Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

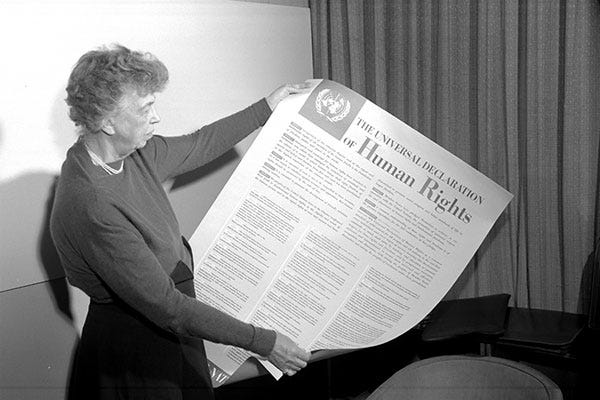

Eleanor Roosevelt at the United Nations (Photo source: nps.gov)

“HYDE PARK, Tuesday—There have been a number of questions showered upon me since I got back from Paris. In fact, while I was away one of the newspapers publishing my column wrote that it seemed rather dull to be told day by day just how each article of the universal Declaration of Human Rights was being written and didn’t I meet some interesting people or do something more entertaining that I could write about.

“As a matter of fact, I purposely described the writing of that Declaration in that way so that people at home might have some idea of the difficulties surrounding the writing of any document which has to mean the same thing in five official languages and, if possible, not really interfere with any of the customs and habits or legal peculiarities prevalent in any of the 53 nations belonging to the United Nations. Judging by the blithe way in which certain groups in our country suggest that we might get together quickly and easily on a world government and accept a rule of law for the whole world, I think some people must have an idea that these legal arrangements are more easily arrived at than is actually the case.”

With these words, Eleanor Roosevelt opened her December 22, 1948, My Day column, written twelve days after the final ratification of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations General Assembly. Eleanor wrote with authority. President Truman had appointed her to the United States’s UN delegation in December 1945. Two months later, UN Secretary General Trygve Lie appointed her to a nine-member “nuclear”commission charged with creating a formal human rights commission. When the commission convened in the fall of 1946, it named Eleanor its chair.

The commission’s charge was not for the faint of heart. Conquering Allied forces revealed the horrors of Nazi concentration camps to the world following the Nazi’s defeat in May 1945. Josef Stalin was creating a sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. Mao Zedong and his communist forces would complete the revolution they began in 1927 with the takeover of mainland China in 1949.

“You will have before you the difficult but essential problem to define the violation of human rights within a nation, which would constitute a menace to the security and peace of the world and the existence of which is sufficient to put in movement the mechanism of the United Nations for peace and security,” Henri Laugier, the assistant secretary-general for social affairs, told the commission at its first official meeting.

“You will have to suggest the establishment of machinery of observation which will find and denounce the violations of the rights of man all over the world. Let us remember that if this machinery had existed a few years ago . . . the human community would have been able to stop those who started the war at the moment when they were still weak and the world catastrophe would have been avoided.”

Henri Laugier (left) and Jan Stanczyk both from the UN Department of Social Affairs, chatting informally with Eleanor (Lake Success, NY, 1947) (Photo source: fdrlibrary.org)

Eleanor proved to be a dedicated and indefatigable chair. She demonstrated a keen appreciation for the cultural and political differences represented across the spectrum of nuclear commission members, which included representatives from Norway, France, Belgium, Yugoslavia, Peru, China, India, and the USSR (now Russia). Eleanor brought the same level of diplomacy to the full eighteen-member human rights commission. She maintained an exhaustive schedule of travel, meetings, and review of draft documents.

Differences among nations were significant. Lesser developed nations were more concerned with economic and social development than they were with human rights. The Iranian delegate told fellow delegates that freedom of speech in the hands of an illiterate population was a recipe for chaos. He believed the HRC should promote literacy before attacking issues of civil and political rights, which the economically developed nations stressed. Eleanor navigated these challenging diplomatic waters with a steady calm and resolute sense of purpose.

By her own admission, Eleanor drove her fellow commission members hard, often keeping them at work from early morning to after midnight. She endured meetings which repeatedly covered the same ground. She looked for ways to bridge the divide between her desire to see the declaration phrased in laymen’s language and her more legalistic colleagues. After extensive commission debate and repeated editing, the Human Rights Commission submitted the finalized declaration to the full 56-member United Nations on December 7, 1948. Three days later, at midnight, December 10, the declaration was adopted in a 48 to 0 vote (the USSR, its allies Byelorussia, Ukraine, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, and Saudi Arabia and South Africa abstained). When the delegates responsible for crafting the declaration were recognized, they rose to give Eleanor a standing ovation.

US Representative to the United Nations (and former first lady) Eleanor Roosevelt holds a copy of the newly ratified Universal Declaration of Human Rights. (Photo source: un.org)

One only need read the reports of Eleanor’s dedication to the Declaration of Human Rights to appreciate the major accomplishment it represents. While not legally binding on the signatories, the declaration is a significant achievement in unifying disparate governing ideologies in the acknowledgment that, in the opening words of the Declaration:

“Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world….”

Eleanor expressed her optimism that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “may well become the international Magna Carta of all men everywhere.” Her hope remains a work in progress.

Note: As of 1999, according to the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is translated into the most languages of any document. For the complete text, see https://www.ohchr.org/en/human-rights/universal-declaration/translations/english

To read more about Eleanor’s work to bring about the Declaration of Human Rights, click here.